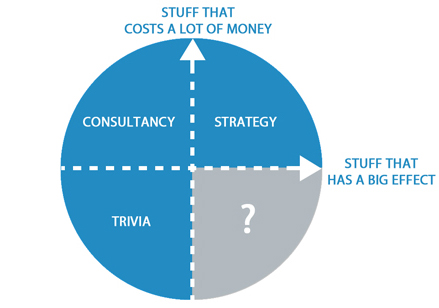

At the end of one of his TED talks titled “Sweat the small stuff,” the perceptive Vice Chairman of Ogilvy, Rory Sutherland, poses a question in the form of a graph (our version below). He asks if anyone can come up with a name for the lower right quadrant. This is where small (and less costly) changes affect fundamental and significant improvements to a large or complex system.

This is a great question, because, as he rightly points out, we naturally expect big changes to come at great effort and cost. We assume there must be proportionality between how much effort and expense an organization expends on something (like its advertising, for example) and the outcome. For some things at some times, I think this is absolutely the case, but to his point, all this effort and expense can also have little or no effect if the essential thrust of the effort is wrong in some critical way.

The “small stuff” is not small at all when it comes to the final execution or the tactical user-level interface.

One way such an effort can go wrong is not taking into consideration the basic truths of human behavior. The “small stuff” is not small at all when it comes to the final execution or the tactical user-level interface. These are the tactical aspects of a design, and their thoughtfulness can spell the difference between success and failure.

So what do you call this thing that does NOT take massive effort but has the potential for great positive effect far beyond its seeming capacity?

I think one very good answer to this question was was provided in 1972 by Buckminster Fuller when he said the following in an interview:

“Something hit me very hard once, thinking about what one little man could do. Think of the Queen Mary—the whole ship goes by and then comes the rudder. And there’s a tiny thing at the edge of the rudder called a trim tab.

It’s a miniature rudder. Just moving the little trim tab builds a low pressure that pulls the rudder around. Takes almost no effort at all. So I said that the little individual can be a trim tab. Society thinks it’s going right by you, that it’s left you altogether. But if you’re doing dynamic things mentally, the fact is that you can just put your foot out like that and the whole big ship of state is going to go.

So I said, call me Trim Tab.”*

The critical task is finding the trim tab. It’s not easy to do. Looking at the Queen Mary from Bucky’s example, if you are an uninitiated observer and do not know what a trim tab is or how the laws of physics and hydrodynamics work, it’s safe to say that it will be next to impossible to guess its importance. Yet there it is. To quote Peter Senge from his seminal book on organizational learning, The Fifth Discipline, “Small changes can produce big results—but the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious.” For an organizational leader, thinking can therefore be as important as doing.

You can watch my explanation of the trim tab in the video below:

In every organization, in every process, in every system there are things that can be discovered that can act as a trim tab.

Rory Sutherland, in a different talk, offers up the United Kingdom’s Royal Mail system as a negative example of what he’s talking about. Apparently, their well-intentioned attempt to improve their 98% next day postal delivery performance to 99% resulted in their spending huge amounts of effort and money to almost no effect. As he tells it, this almost killed them. This improvement was an obvious and well-intentioned thing to do. But it was like seeing the Queen Mary heading in the wrong direction and doing the most obvious thing: push on the bow of the ship to make it change course. The amount of energy required to make a great ship change course by pushing on its bow is, in fact, astronomical.

He rightly suggests that what they could have done—at considerably less cost and no institutional turmoil—would have been to advertise the fact that at 98%, the Royal Mail system’s next day mail was, in fact, already better than the comparable service in Germany. Perhaps this is not really a trim tab solution, since advertising is still expensive and involves a good deal of effort, but it does illustrate the point.

During the Bronx Museum Free Campaign that we completed recently, one of the least expensive and most effective aspects of the effort was to modify the signage on the building itself. The Bronx Museum needed to engage local residents more effectively and wanted more of them to walk through the front door of the museum. They got funding from the city to make the institution free, and we did an outdoor campaign to support this announcement, but it was the signage on the building itself that did the most to actually drive local residents through the front doors.

The original building signage was too high for pedestrians to actually notice. Many people walking by the building—even those walking by every day—did not know what it was. By putting large, brightly colored signs in the street side windows of the museum—and on the front door—we increased the foot traffic in the museum enough that we had to modify the signs to clarify which days the museum was closed, because too many people were coming in on those days and bothering the guards.

If you can find a trim tab in your quest for improvement, then everything else can be made easier and more effective.

If we want our work to matter, we must recognize the critical importance of taking the time and making the effort to think through the tactical user-level interface. In developing an organizational brand or devising a marketing plan, the work’s ultimate effectiveness can be traced directly to discoveries that have been made along the way. If you can find a trim tab in your quest for improvement, then everything else can be made easier and more effective. Without such discoveries—even if you have plenty of money—the outcomes can still take you next to nowhere.

So I would say that the word to fill in the blank in Mr. Sutherland’s graph is “trim tab.” What do you say?

Click below to sign up for our mailing list and get access to our library of downloadable guides, including this one on the trim tab:

Photo credit: “Bucky TRIMTAB.jpg” by Shriramk is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5

Ask for help.

We are kind, thorough and ready when you are. You just need to ask.