Artist Branding, Kate Nash, and a Question: Can You Name Five Women Artists?

I took my 18-year-old daughter to a Kate Nash concert earlier this week. My daughter arrived ahead of me. Her text: “Only middle age people.” We stood in the line debating the meaning of “middle age.” Neither side won, but I learned two things about her perspective: a) anyone out of college, like most of the people at the concert, can be categorized as “middle age” and b) “middle age” is based on productive life expectancy—so in my early 50s, I am well past middle age.

The concert was fantastic and also provocative because it got me thinking about artist branding. I promise I’ll get back to the inimitable Kate Nash in a minute.

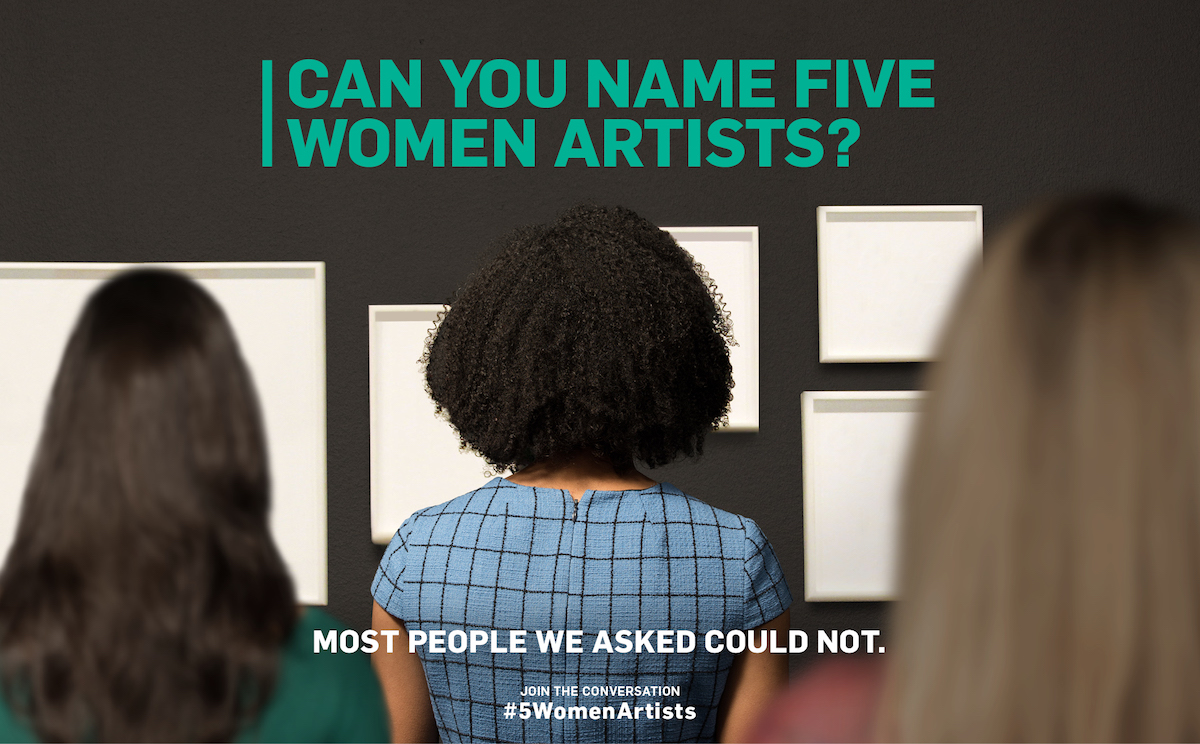

Can you name five women artists?

We recently launched a brand advertising campaign for the National Museum of Women in the Arts. It poses the question “Can you name five women artists?”

I think the campaign exposes significant issues in the arts as they relate to artist branding. To set some context for this, please note that all brands accrue power through differentiated simplicity. They must be at once distinctive and easily grasped. In general, the further these two factors can be optimized, the better, provided that the brand is satisfying a need of a particular set of customers.

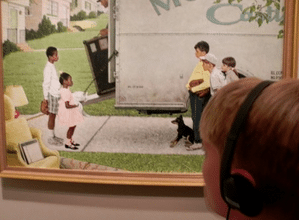

When we ask the question “Can you name five women artists?” most people have trouble, then they sort of freak out at the realization that they can’t do it. It seems to simultaneously expose the gender inequality of the art world and also our complicity in that inequality. “Why don’t I know five women artists? What’s wrong? Something is wrong.”

The following metaphor might be an overstatement but only a slight one: We are all fish swimming in water. “Water” is the male domination of nearly every field of human endeavor. “But I’m a fish. Water just is. I am a fish. What is swimming?” Then it hits you: “I’m swimming.” For women or for any feminist, it may be like that. “Oh, I’m a willing, unwitting participant and collaborator, aren’t I? I can name Picasso, Matisse, Van Gogh, Warhol, Mondrian, Rembrandt, and many more. But I get stuck after Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keefe. WTF?”

Remember: simplicity is power in any brand.

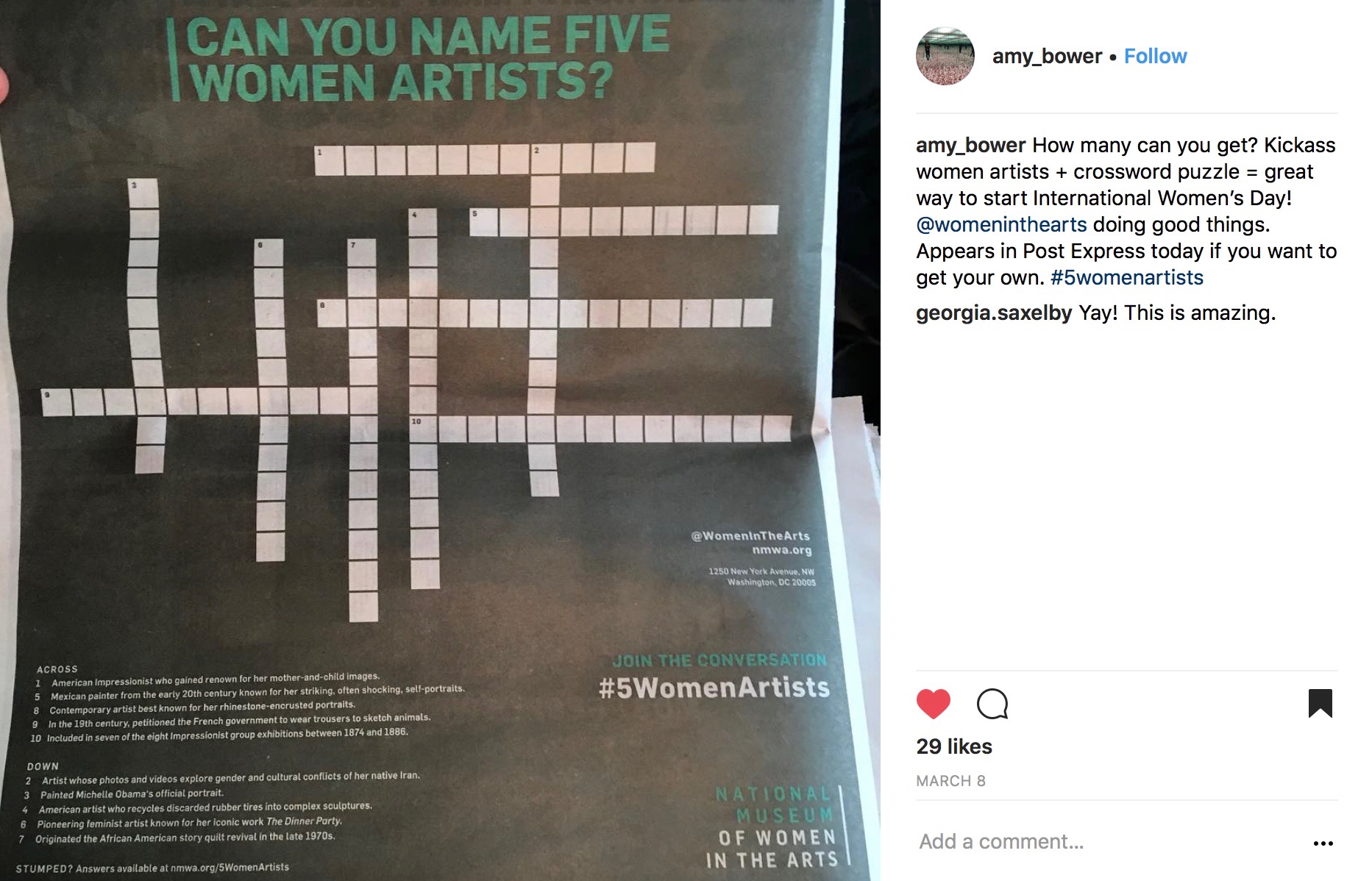

There is another dimension to this. You will notice that in the list I gave, all these well-known male artists are recognized by a single name. Pablo is not needed for the Picasso brand to form in your mind. Remember: simplicity is power for any brand. Men get special privilege even here on the level of brand—they (many of them) get to be known by just one name (sorry Chuck Close). Do any female artists get this same privilege? They do not. Mary Cassatt? Judy Chicago? Yoko Ono? Barbara Kruger? Chakaia Booker? Yayoi Kusama (maybe just Kusama because the whole thing is plain difficult for Americans)? Women face an uphill battle in establishing themselves as artists (and also brands—more on that below) if the answers to “Can you name five women artists?” are any indication.

Think of this crossword puzzle that we ran as part of the campaign for the National Museum of Women in the Arts. If the puzzle were for all artists, not just the women, then the men would be so much easier to guess. Their names would be half as long, twice as simple.

Artist Branding

Artists don’t usually think of themselves as brands. I’m sure the idea chafes. “I am an artist” is an assertion against branding and its requisite responsiveness to customer demand. The idea that an artist is free from commercial considerations when it comes to their creative work is important and, I’m sure, deeply held by most artists. One could say this is a romantic or naive belief, but I think it is essential for many artists. The distinction between art and commerce is meaningful and worthy of preservation, but that does not impede the inexorable operation of brands or their propensity for simplification. It is key to any brand’s power. So despite all protestations to the contrary, artists are brands. At least the successful ones all are. Tell me Picasso is not a brand, intended or not. The Beatles? Roll over Beethoven, Mozart, Verdi!

The artists we know are brands because we make them so in our minds. That’s how we organize and remember them. Each holds a differentiated position that we value and each has an associated brand name. They all operate as brands because they effectively conjure up some particular and consistent thing in our minds, something triggered by a visual or musical style, a set of notes or a type of brush stroke, or simply by the mention of their name. This is powerful stuff and artists should not ignore it out of pride. The pain in the ass of it is real though.

Artists don’t usually think of themselves as brands. I’m sure the idea chafes. “I am an artist” is an assertion against branding and its requisite responsiveness to customer demand.

Who would want their life’s work reduced in this way? We are all complicated, we all contain multitudes, and yet what we are talking about is the equivalent of typecasting. Once you become known for something, that becomes “who you are.” Of course, it is not nearly all of who you are, and yet the stronger that thing is, the more likely it is to come up in people’s minds; this is what builds and reinforces a brand. On the inside, I’m sure it feels like a trap or a cage, but the unfortunate reality is that in the grand scheme of things, anonymity is the only other option.

I have often thought that it would be tiresome for a musician to always be asked to perform their greatest hits. “Beethoven, can you play the Moonlight Sonata again?” The pressure to do this is derived from the intense desire to have an artist reinforce the brand that is the basis of our affinity for them. It is why we identify with or support that brand rather than this other one. We want reassurance from the brand that it still loves us. We are needy.

It’s sad, but so it is.

Kate Nash

Enter Kate Nash. I immediately loved her authentic, funny, in-your-face feminist attitude, but as a passive fan, I just listened and enjoyed her music as it came up on my Kate Nash Pandora channel.

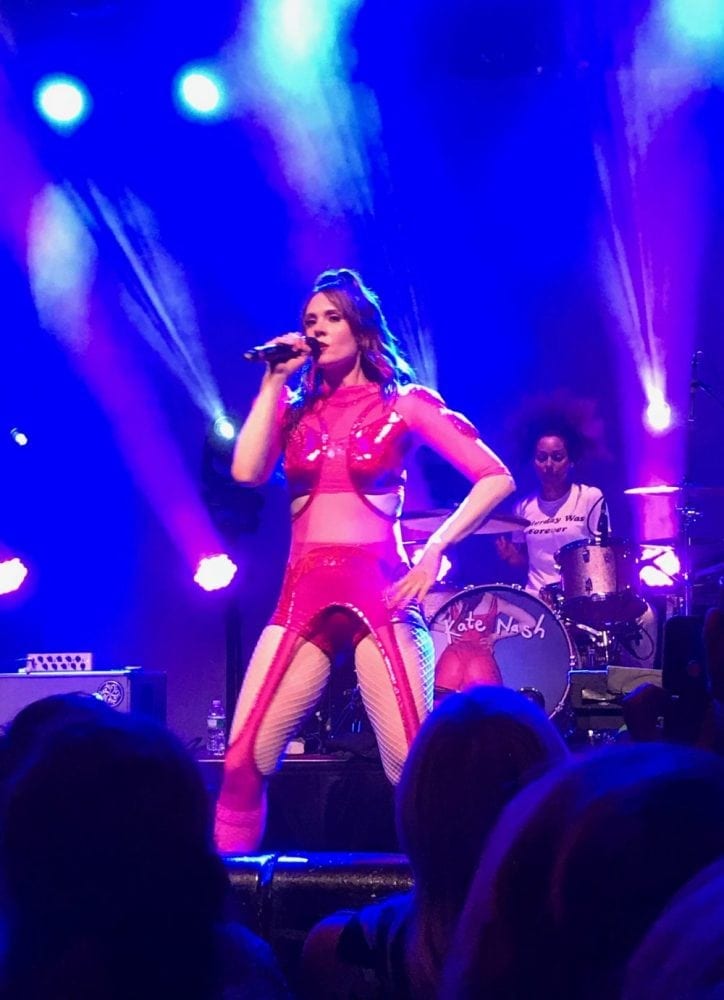

Here is a good illustration of the Kate Nash brand I had in my head. It’s her at 20 singing her chart-topping hit “Foundations.” She’s a spunky, snarky variant of the singer-songwriter, accompanied by an unassuming bandmate.

She held this special brand position in my mind and I left her there over the intervening years. Why would I change the space she occupies? Because it would require mental effort to do so? In Kate’s own words from a recent LA Times profile, “People don’t know anything unless you shove it down their throats.” We are all lazy this way. A brand gets positioned on a particular shelf and we leave it.

On Wednesday, I was brought up to speed. Seeing her in concert pulled the Kate Nash brand off that shelf and put it on another, higher one. I encountered, with my daughter, the full girl-power, feminist, “let’s-change-the-world” force of the Kate Nash brand. This got me excited because the whole room was excited about that too. And she was now a full-on rocker with a self-proclaimed all-girl band (clearly she does not regard herself as middle-aged quite yet). This new (for me) Kate Nash is the perfect combination of passion in performance backed up by talent and yet, still without artifice (an essential component of her original brand).

To quote from Sad Girl Jams on Instagram: “Seeing Kate Nash was one of the most joyful experiences I’ve had in a very long time. There’s something indescribably energizing about how it feels to watch a bunch of super talented women on stage being unapologetically themselves, and I’m SO happy to have gotten to share in the last night of this tour!”

I was witnessing positive magic and this time, performing that same song, she was crowd surfing a packed and enthusiastic New York City concert hall. (My iPhone footage captures a bit of the feeling.) She’s pushing through a brand transformation that I find exciting. In doing so, she certainly made her core customer—loyal fans in New York among them—very happy.

So there is nothing we can do about the reductive quality of brands and the branding that we all do in our minds. As an artist, as a business, as a nonprofit, you have to acknowledge and respect that reality, but you can rebrand. You can evolve your brand to be a bigger, better, more impactful version of what you stand for in the world. You can have an impact, and your brand must be your ally and friend in this endeavor.

___

Tronvig Group Creative Credits:

Art Directors: Sarah Ahrens, Florencia Garcia & Anne Mieth.

Creative Director: James Heaton

It’s a good article.

Funnily enough Kate and I were discussing her fans’ ages on the night of that gig. The press were always complaining her fans were teenage girls, as if there was a problem with teenage girls. When she first started she was a teenage girl herself. But she always had older people in the audience, including men.

We mentioned at the gig she still had a lot of teenage girls, who knew all the words of her songs, pretty much all of them and wouldn’t have been around the first time. They’re a loyal bunch.

The NY crowd were something else. Really amazing. Loved the gig.

Thanks! It’s funny because I brought both my daughters to Kate Nash when they were teens (They are now 18 and 20), but I was consciously introducing Kate’s music to them, because I wanted them to know it. The music clicked and stuck—which is not true of most things I might try to introduce them to. I’m working on my son. We need feminists of every age, gender and disposition!

We certainly do. All my girls are feminists. And so is my husband. Having 3 strong daughters means you almost have to be.

I love the article, it was my goddaughter, another strong young woman, who shared it with me.

When Kate first got into this business the press were all about personal questions, about family, friends, fashion and boyfriends. When the same press interviewed her then-boyfriend, who was also in the music business, it was all about the music.

We have to always be aware and fight prejudice of any sort wherever we find it.

Wow. We still have so far to go. It sometimes feels we’ll never get there. But you must be very proud. I think of Kate now as being part of what E.M. Forster called “an aristocracy of the sensitive, the considerate and the plucky. Its members are to be found in all nations and classes, and all through the ages, and there is a secret understanding between them when they meet. They represent the true human tradition, the one permanent victory of our queer race over cruelty and chaos.” Kate is making a difference.

Good read and lots of questions, where does one start!

I now have a few private comments like this one: “Good write-up (as always!). But Cher, Madonna, P!nk come to mind as female musical artists recognizable by only one name.”

I cut a section out of the article. I did this for length and to trim the number of points I was attempting to make in one piece, but I guess something needed to be there, so back as a result of a concerted letter-writing effort:

So what about Madonna or performing artists in general? Beyoncé, Melanie—there are certainly performing artists who have succeeded in getting their brands distilled to one name.

Visual artist vs. performing artist: What is an artist? The strongest association for the word artist is arguably visual artist: painters, sculptors, and the like, and our brand ads for the Women’s Museum certainly reinforce this. So while the question we asked about five women artists does not specify any particular kind of artist, the strong implication is that we are only asking about visual artists. We could not find our way around this dilemma in our version of the campaign, and our client, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, operates primarily in the art world despite the more open-ended “Arts” in their name.

The branding issues I’m working on here certainly pertain to both kinds of artists (as Marie Nash’s comments above about Kate’s experience with the press exemplify). People can name five performing artists (I would hope), but all the other issues of inequity are fully parallel.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts documents the statistical litany of the art world inequity: https://nmwa.org/advocate/get-facts

What about Hollywood? Much the same: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/01/the-brutal-math-of-gender-inequality-in-hollywood/550232/

The music business? https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/25/arts/music/music-industry-gender-study-women-artists-producers.html

This was where I was going with “the male domination of nearly every field of human endeavor.”

I was JUST writing about the same phenomena that you discuss here. In a written interview last week I was asked what’s my favorite picture book(s)—off the top of head, my favorites are written and illustrated by men. In response to a later question I noted how it’s always men who immediately come to mind when I am asked to list my favorite illustrators. Even though I know a number of women illustrators, I have to pause to remember them. In all the children’s books conferences and events I attend, 85+% of my fellow attendees are female, but 70% of all Caldecott winners are male. And nobody can give a satisfactory answer as to why men have so much more success than women in the picture book industry, especially when the gatekeepers—the editors, librarians, educators—are predominantly women.